In 2016, eBASE Africa a JBI affiliated group in collaboration with CamCoSo a Cochrane affiliated consumer group in Cameroon, started work with traditional story tellers, poets, singers and dancers to increase uptake of research evidence. This was true to eBASE Africa’s mission to improve livelihoods through innovations and best practices in underserved populations. eBASE Africa had noticed the difficulty in translating research evidence to rural communities and indigenous populations in Africa who were most often not able to read and write. It also considered the fact that communication through arts has been ingrained in the African culture and would be a good approach for evidence translation.

The innovative evidence translation approach was titled ‘Evidence Tori Dey’ which is a term in pidgin meaning ‘Lets talk evidence’. Pidgin is widely spoken across west and central Africa. Between 2016 till date, eBASE Africa has worked with consumers and story tellers to translate research evidence from Campbell collaboration and Education Endowment Foundation to improve attainment in basic and secondary education; Cochrane collaboration and Joanna Briggs Collaborations to improve health outcomes related to malaria in children under five years of age; and Canadian International Center for Disability and Rehabilitation recommendations to address rights and psychosocial needs for people living with disability. This approach decrypted an existing phenomenon of evidence hesitancy in consumers.

What is ‘Evidence Tori Dey’?

Evidence Tori Dey is an evidence translation approach developed at eBASE Africa to help communicate research evidence in the basic services to a more diverse group of people. It uses results from research evidence using GRADE frameworks and JBI FAME (Feasibility, Appropriateness, Meaningfulness, and Effectiveness) models to develop evidence-based story points. These points are then used by story tellers to develop stories about evidence.

The approach is based on 2 principles:

-

Arts is an engrained approach of communication in African culture. This could be in the form of stories, poems, songs, dance, or graphics. The message is usually communicated in a less confrontational way especially when we intend to achieve a change in behavior.

-

High rates of illiteracy in especially in rural communities and indigenous populations. This means that reading evidence summaries may not be possible.

At eBASE, we have worked in collaboration with consumer groups and story tellers to translate evidence in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria, SGBV, behavior management in schools and school exclusions, and stigma in HIV.

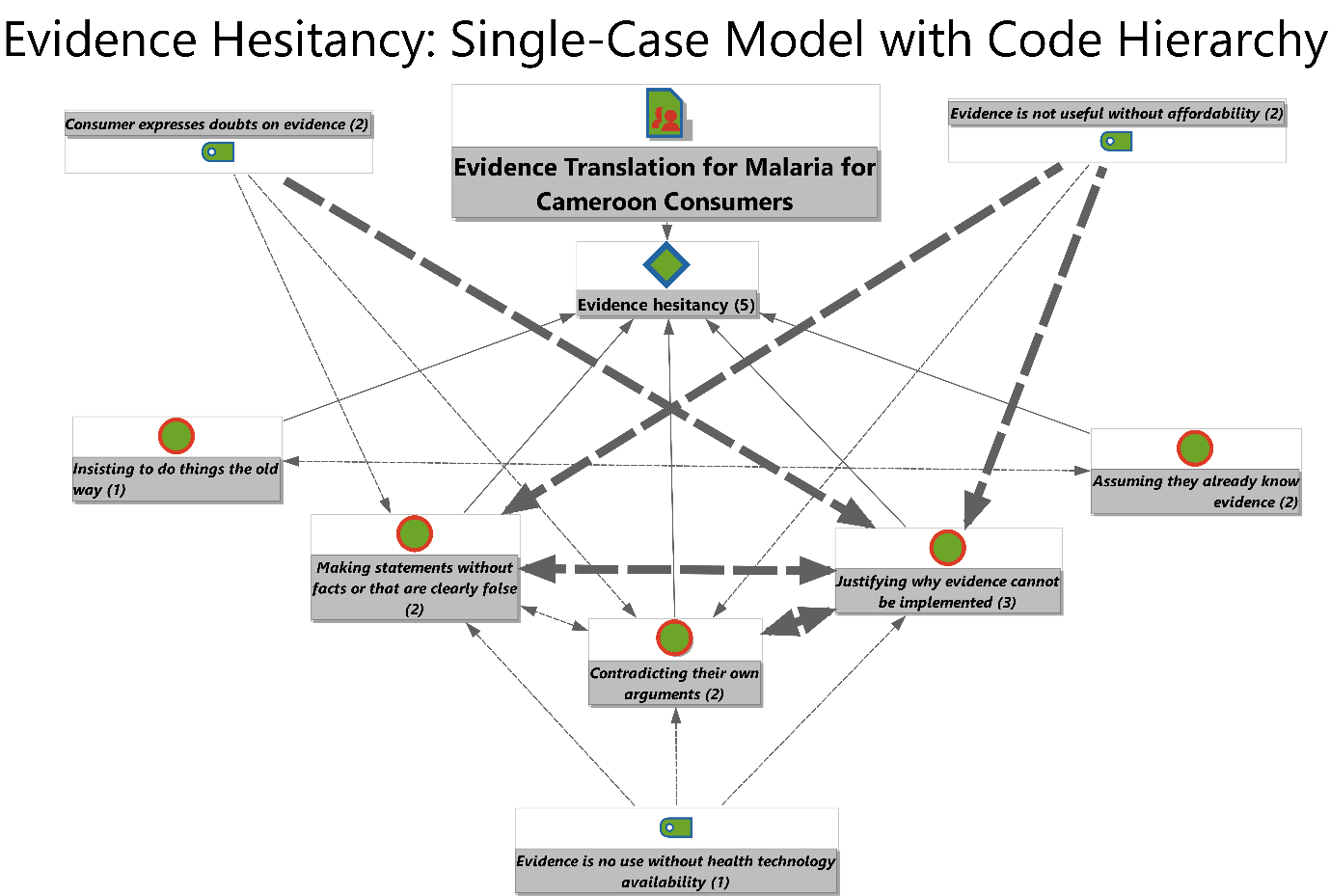

What is evidence hesitancy?

At eBASE Africa, we define evidence hesitancy as ‘The failure to accept evidence-based recommendations quickly or immediately usually because of an underlying reason which may be immediately known or unknown’. Evidence hesitancy is a phenomenon that has been identified in our projects when we implement our evidence stories from policy makers, practitioners (teachers, doctors, nurses, development workers etc.), and consumers.

Evidence hesitancy may be the biggest threat to uptake of research evidence in our experience. In an exit qualitative interview conducted with viewers of evidence stories on the management of uncomplicated malaria, we identified that There were 3 main reasons for evidence hesitancy:

-

Technology required for evidence implementation is not available: consumers complained that even when they wanted to do a test for a fever before treatment, the equipment or staff needed to run the test were not available and they could not wait till one was available.

-

Technology required for evidence implementation is too expensive: consumers complained that they cannot afford both testing and treatment, they will therefore prefer to spend all the money on treatment

-

Preference in doing things the old-fashioned way – eminence-based practice – some participants mentioned that they have always bought roadside meds to treat their malaria and didn’t need to do a test, and for them this has always worked.

Challenges

The main challenge with Evidence Tori Dey is funding to fully develop the concept and travel to hard to reach communities including rural areas, indigenous populations, people with disability and non-literate populations. This requires more than just systematic development and dissemination of stories, but a more active approach of seeking out, reaching out, and influencing policies to ensure no one is left behind. This approach has so far been developed at eBASE Africa a Joanna Briggs Affiliated Group in collaboration with CamCoSo a Cochrane affiliated consumer group and La Liberté Arts Group in Cameroon, without funding.

Discussions

Reaching out to underserved populations with best practices remains a challenge for policy makers, development agencies and practitioners. This is largely due to the fact that business as usual in evidence dissemination world has been structured for the regular population. Community members who cannot read, or who have reading difficulties, or live in rural areas are usually left behind. Consumers must understand the evidence behind best practices to be convinced about using it. Policy makers must understand the evidence behind best practices to convinced to make evidence-based technologies available and affordable.

Upcoming Events

eBASE Africa will be presenting these concepts at the upcoming Cochrane Colloquium in Santiago, Chile from the 21st to the 25th October 2019. www.colloquium2019.cochrane.org

The views expressed in published blog posts, as well as any errors or omissions, are the sole responsibility of the author/s and do not represent the views of the Africa Evidence Network, its secretariat, advisory or reference groups, or its funders; nor does it imply endorsement by the afore-mentioned parties.