If you are interested in this topic, review the webinar presentation or watch the recorded webinar.

This blog post is based on the second webinar of the Evidence 2023 capacities webinar series hosted by the Africa Evidence Network (AEN). The AEN Evidence 2023 capacities webinar series aims to create a platform for sharing experiences and ideas that push our thinking on how (approaches) we enhance capacity for evidence use in Africa. The series also strives to generate ideas on the implications of novel approaches for wider ecosystem strengthening efforts. It is also our hope that these discussions will be the basis for improving and illustrating the AEN's Manifesto on capacity development for evidence use in Africa.

An earlier post in the webinar series highlighted innovative approaches being deployed for EIDM capacity development in Africa. This post follows-up by capturing salient points from the second webinar in the series, unpacking the implications of these innovations among various stakeholders within the evidence ecosystem. The webinar series is being held by the Enhancing Evidence Capacities Working Group as build up to the much-anticipated Evidence 2023 in September 2023.

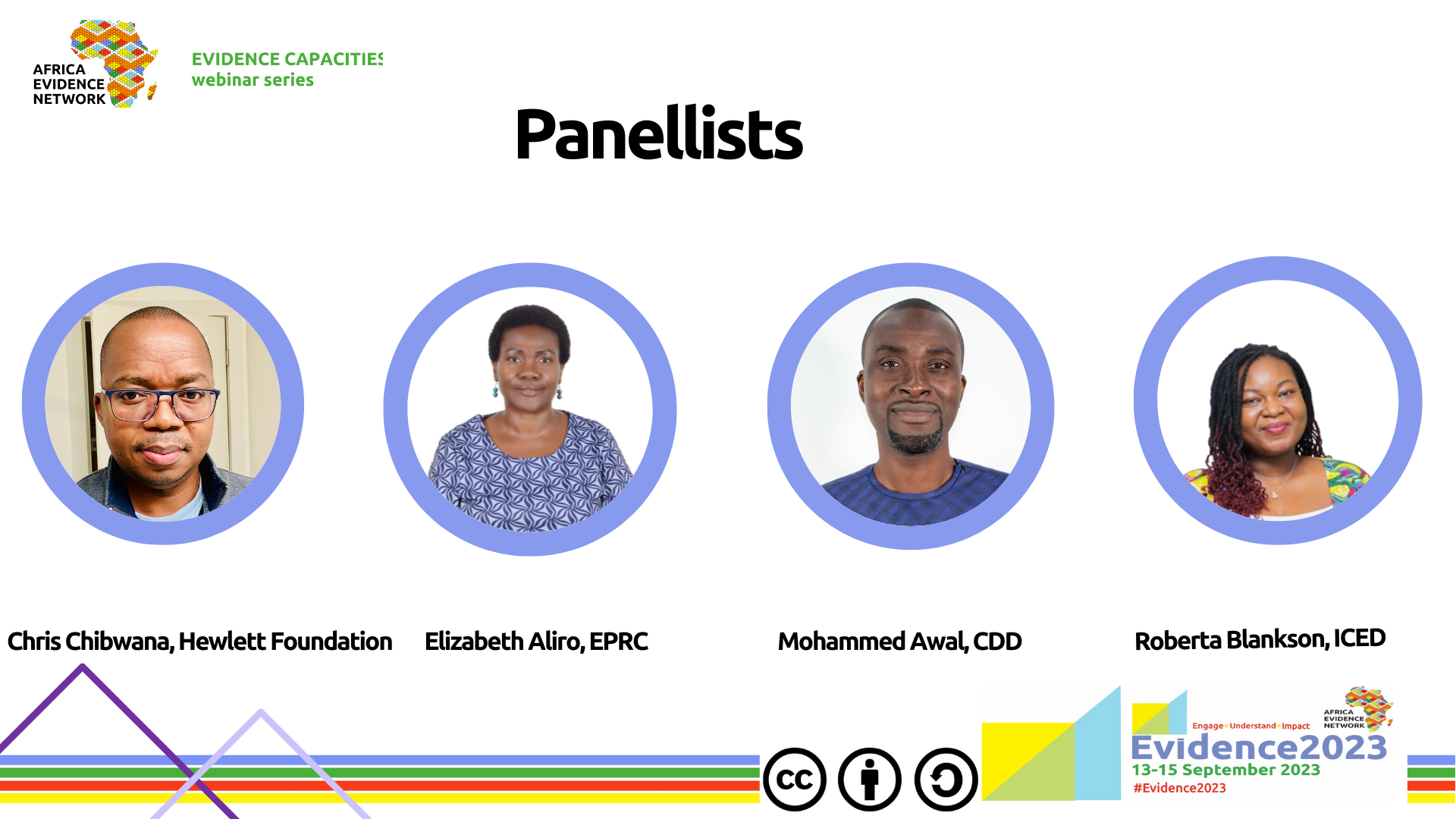

Panel of speakers

The session was chaired by Siziwe Ngcwabe and moderated by Kirchuffs Atengble, both co-chairs for Evidence 2023. The speakers included Chris Chibwana (Hewlett Foundation, United States of America); Elizabeth Aliro (Economic Policy Research Centre, Uganda); Mohammed Awal (Centre for Democratic Development, Ghana); and Roberta Blankson (International Centre for Evaluation and Development, Kenya). They represented stakeholders playing diverse roles within the evidence ecosystem including funders, producers, intermediaries, and consumers.

Perspectives on EIDM roles played within the ecosystem

Elizabeth kicked off the discussion by highlighting that as a think tank her organisation produces evidence for the government and the wider audience of development stakeholders. Through technical assistance to government agencies and development partners, they enhance the capacities of these stakeholders to facilitate evidence uptake. Knowledge brokerage is another role they play by analysing national data to answer policy questions and make recommendations. A fourth role, though to a lesser extent, is to consume evidence, as they generate knowledge products.

Mohammed shared that his organisation, also a think tank played similar roles as Elizabeth had described. In their role as producers, his organisation collects evidence, which includes citizens’ perspectives and evaluations of government projects. As intermediaries, they play an advocacy role with various actors to facilitate strengthening of the evidence ecosystem by addressing prevailing challenges, through the development of standards for data, and expanding the data sources used as evidence, among others. Similarly, they also function as consumers within the ecosystem.

Chris pointed out that his organisation’s role is primarily to fund the producers and intermediaries within the evidence ecosystem. Their strategic approach is to support African policy research institutions to foster regular use of evidence by governments, and for researchers to generate evidence relevant for policy decision-making. Additionally, they also support the establishment of national and regional communities of practice around EIDM, such as what AEN is doing. He also shared that they facilitate the elevation of the status of African think tanks to enable them to participate in policy discussions locally and in the global space. He highlighted his organisation continues to support capacity enhancement because of the belief that capacity (across the spectrum of actors and their levels) is fundamental within the evidence ecosystem to facilitate EIDM.

Roberta shared that she also represented an international think tank that plays roles as producers and intermediaries within the ecosystem. They collaborate with members of parliament, researchers, and funders to enhance their capacity for EIDM. She highlighted the interwovenness of these roles in that, as an organisation, they find themselves acting as producers, intermediaries and users, echoing sentiments shared by Elizabeth and Mohammed.

Implications of innovations in EIDM capacity development across the ecosystem

Roberta opined that for her organisation the emerging innovations meant an increased interest in, and demand for, evidence use over time, along with institutionalisation of using evidence for decision-making. Additionally, it also means a paradigm shift towards having African-led research informed by context-relevant priorities. To her organisation, this meant going beyond training to providing grants, supporting institutions to manage large grants and the research process from end-to-end. Having acquired these capabilities, the institutions are able to bid on their own and conduct the research projects. Additionally, they support in their use of the evidence to support learning about the implementation process and facilitate collaborations between different ecosystem players to promote scaling up for higher impact as opposed to duplication of efforts.

Mohammed associated with Roberta’s reflections but highlighted that for his organisation it meant enhancing these capacities at the subnational level which has more direct impact on the lives of citizens. Implication of this is the needed enabling of actors in this level to responsive to the citizens’ needs and feedback. He illustrated how they aim at bringing more structure into policy dialogues; enabling in effect the focus on key development issues and addressing challenges with availability of evidence that enriches policy decisions. This spans from their capacity to set the research agenda, to generating local evidence that is responsive to emerging research questions. For his organisation’s target audience, he theorised that these innovations meant an added layer of work – determining the impact of their work on targeted communities, all within structural or bureaucratic constraints they operate in.

Elizabeth introduced a new perspective regarding the focus of capacity enhancement interventions on technical skills at the neglect of soft skills such as motivation and cultures which influence evidence use. This is an area of emphasis for EPRC. She went further to state that her organisation seeks to unearth the extractable lessons from existing capacity enhancement interventions which they can adopt and adapt to design interventions for the African context.

Chris highlighted that the discussions foregrounding the promotion of organic solutions to address local problems made him optimistic. This is because of Hewlett’s strong belief that proximate actors in the evidence ecosystem are key to effective and sustainable capacity enhancement for EIDM by decision-makers. He however placed a caveat that there is need to ensure effectiveness of the interventions, and in the absence of existing evidence endeavour to generate this evidence. This, he emphasised, is an important determinant of gaining support from funders who need to decide how to efficiently invest the limited resources available. He also called for ‘right-sizing’ the capacity gap and the appropriate intervention to address it, while encouraging sustainability thinking in intervention design by enhancing capacities at the organisation level in addition to individual capacities.

Questions and answers

In responding to a question from the audience, Roberta pointed to time as a key constraint to demonstrating results from interventions, as the brief implementation timeframes may not allow interventions to mature and begin to bear fruit. She added environmental constraints such as geopolitics as an additional factor, which can hamper the implementation processes.

As a funder, Chris acknowledged the constraining effect of limited funding cycles required for capacity enhancement interventions to yield expected results such as sustainable relationship-building. He reemphasized the challenge of failure among EIDM capacity builders to be pragmatic in right-sizing the capacity gaps and interventions. He recommended that measurement parameters to demonstrate impact need to be considered carefully based on whether they have the capacity to demonstrate an actual change. Mohammed emphasised the importance right-sizing interventions to ensure measurable impacts, and investing more on organisation-level EIDM capacity enhancement for sustainability.

A second question sought to understand whether there is a relationship between those who set the research agenda and the funders. Mohammed responded by indicating that such a relationship is paramount in the process of decolonising EIDM, so that the evidence is relevant for addressing local needs.

Another question touched on increasing the involvement of conventional evidence-users in co-producing evidence. Elizabeth affirmed this because of the increasing adoption of co-creation within the practice. This shift has resulted in the narrowing of boundaries and strengthening of relationships among diverse evidence ecosystem actors, and impacts positively to promote evidence uptake.

Chris was asked to highlight examples of capacity enhancing interventions that funders are enthusiastic about. He intimated it was necessary as a starting point for capacity enhancing organisations to identify internal capacity constraints required for execution and proceed to engage funders on these capacities. Further, he encouraged connections within ecosystem players within this much siloed space.

Closing reflections

In closing, panellists were invited to reflect on innovative capacity enhancing interventions and the AEN Manifesto, aiming at generating insights to refine the latter. Mohammed emphasised the need for localising interventions and their learnings to inform future work on EIDM capacity enhancement.

Elizabeth’s concluding remarks revolved around the need for clear parameters that define interventions and having clarity about what interventions work in specific contexts through documentation of the evidence. Inclusivity and equity are important principles that also need to be integrated into EIDM capacity development interventions focusing on minority and marginalised groups, such as persons with disability.

Chris reiterated that the Manifesto needs to emphasise capturing and documenting evidence on EIDM capacity development interventions to encourage ecosystem players not to ‘preach water and drink wine.’ Roberta highlighted the need to foreground knowledge management for sharing of lessons, creation of repositories, building collaborations that augment synergies to scale up rather than duplicate.

Further reflections beyond the webinar

To build on the insightful discussions during the webinar, some additional questions to mull over are listed below. Feel free to share your thoughts as you respond to them.

- What are some of the opportunities around knowledge management to keep this learning available and accessible at the organisation even if the staff leaves the organisation?

- In the last few years, there has been an emergence of capacity development initiatives for evidence-use in the UK and Europe. Using some similar approaches to those that the AEN members take, how can African innovations learn from these new initiatives?

- Who dictates the focus of your research or the evidence that you produce?

- Are capacity building efforts focused on generation of Africa-specific solutions or copying the West? Do we have unique solutions for Africa's development given its unique problems?

- How do we ensure that evidence is incorporated in our political Manifestos for proper implementation?

About the author: Dr. Jacklyne Ashubwe-Jalemba is a Medical doctor with fifteen years of clinical and public health experience. Jacklyne is a health systems researcher based in Nairobi, Kenya. She holds an MBCh, B and MSc in Tropical and infectious diseases both from the University of Nairobi. She is a public health and knowledge management consultant and the Director at Medwise Solutions, a consulting firm engaged in public health projects’ evaluations and knowledge management capacity strengthening.

Additionally, she graduated from the Management Development Institute (MDI) with a certificate in leadership, management and governance for health systems strengthening an area she is passionate about. Through her work she has garnered substantive experience in providing actionable recommendations after conducting evaluations of public health projects; and facilitated improved organisational performance by providing technical support and capacity development. She has local and international experience in low-and-middle-income countries. The scope of projects she has worked on includes primary health care, reproductive-maternal-newborn-child-and -adolescent health, healthcare quality management, healthcare financing, and digital health interventions. Her work in these projects involved leadership, mentorship, and capacity building of teams to conduct evaluations of multi-lateral-, bilateral- and NGO-funded public health projects and programs implemented at National and County levels. Additionally, she possesses experience in determination of program/ project implementation and effectiveness; and evaluation research methods comprising primarily qualitative methods, but also basic quantitative methods such as descriptive analysis. Her portfolio of clients includes World Health Organisation (WHO), DANIDA, The World Bank and Ministry of Health, Kenya, USAID-funded implementing partners including mothers2mothers, Jhpiego, University Research Company (URC); USAID contractors including International Business and Technical Consultants Inc. (IBTCI); UKAID-funded local project implementers such as Lexlink Consulting.

Acknowledgements: The author(s) is solely responsible for the content of this article, including all errors or omissions; acknowledgements do not imply endorsement of the content. The author is grateful to Charity Chisoro and Kirchuffs Atengble for their guidance in the preparation and finalisation of this article as well as their editorial support.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in published blog posts, as well as any errors or omissions, are the sole responsibility of the author/s and do not represent the views of the Africa Evidence Network, its secretariat, advisory or reference groups, or its funders; nor does it imply endorsement by the afore-mentioned parties.

Suggested citation: Ashubwe-Jalemba J (2023) Innovations in EIDM Capacity Development: implications for various stakeholders in Africa. Blog posting on 09 June 2023 that is part of the AEN blog series on the Evidence 2023 Capacities webinar series. Available at: https://www.africaevidencenetwork.org/en/learning-space/article/240/