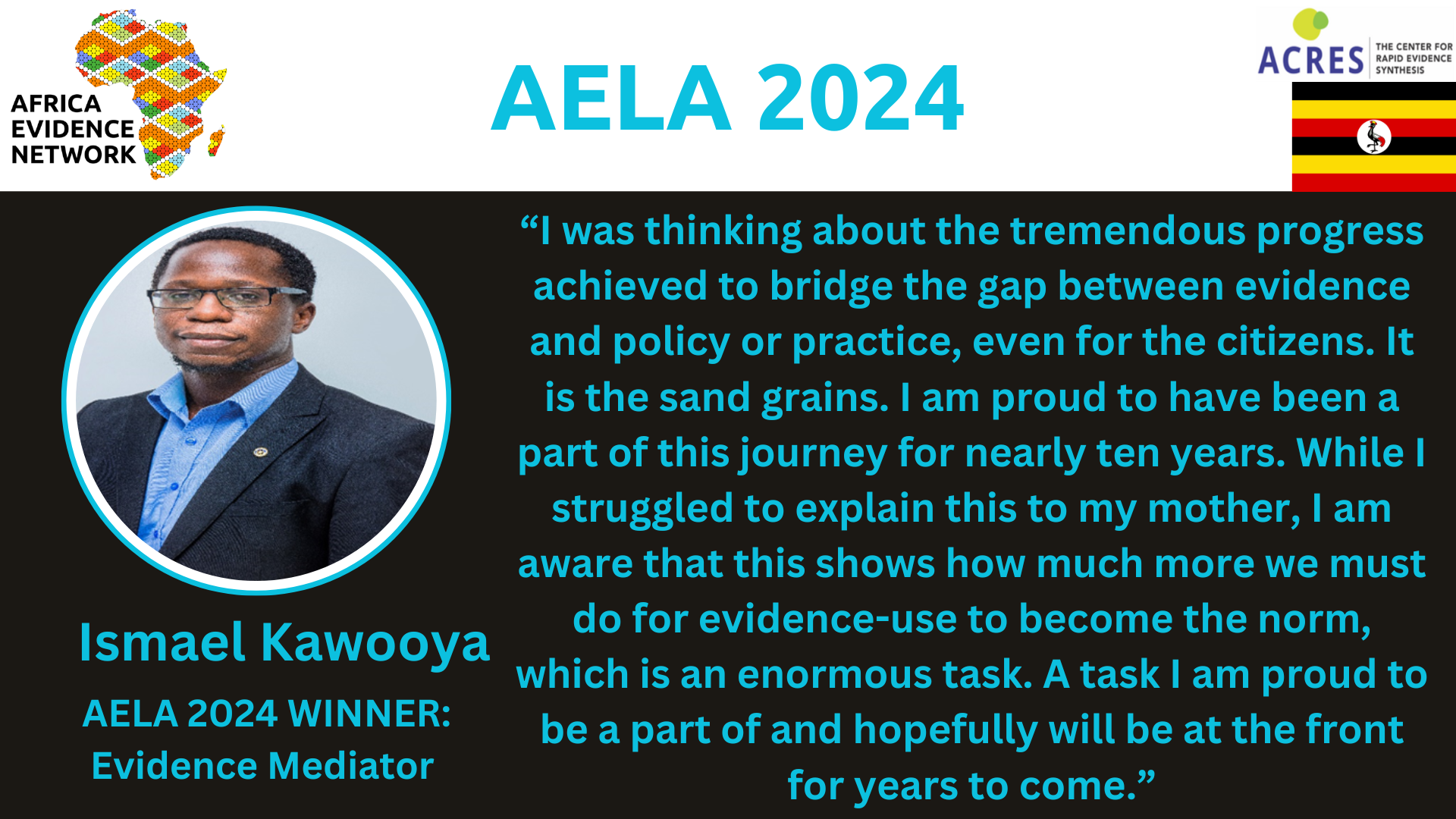

Ismael Kawooya is the recipient of the Africa Evidence Leadership Award 2024 in the Evidence Mediator category offered by the Africa Evidence Network. We asked Ismael to reflect on his work.

A medical doctor in a “typical” Ugandan society has unique perks. One gets a seat at the high table at any community event, sometimes without additional asks. The master of the ceremony has to recognise the medical doctor’s presence. Well, that was before Covid-19. Now, everyone has become a “doctor” or “epidemiologist”. I suppose this was mainly from a lack of access to relevant information - be it finding or understanding the available evidence. Situations like this increasingly show the need for those who operate on the nexus of evidence and policy or practice. However, the communities are often left alone or for others to fill the gap, often with skewed interests. The updated Global Evidence Commission Report 2024 emphasises the importance of evidence at the centre of everyone’s life, even in households.

However, before discussing using evidence in households, how would you describe yourself if you worked at the boundaries of evidence and policy? That would make for an exciting family conversation. A brave soul will often try because everyone ought to appreciate the importance of research, community information, and data. In societies where the majority struggle to read any text, this makes a more exciting conversation—usually to the exclusion of the majority.

Innumerable terms are used to describe the evidence-to-policy phenomena. Similarly, the number of tools is increasing, including evidence syntheses, guideline developments, capacity building, storytelling, rapid response service, and currently generative artificial intelligence, such as ChatGPT. The latter has gained more traction and made it easier for many people in the communities to engage with the evidence. However, there is a need to improve the understanding of how the ChatGPT could learn to provide users with more accurate and critical information rather than being derided for failure to grasp certain tasks. As someone who has worked with the rapid response service for nearly ten years, I am all too familiar with the conversations about why providing well-packaged (simple language or format) and “quality” evidence syntheses for different audiences would be impossible. I can only imagine how much more the world would have benefited had we more collaborators to improve the quality of the service. Whether we use the lessons or not, Covid-19 is important for everyone.

Ordinarily, citizens do not think of policies or how these affect their lives, let alone the “elitist” terms, unless they are interfacing with the state. Social media, with all its negatives, has catapulted the information age forward. It is no longer unusual for politicians, even a president (President Ruto of Kenya), and government technocrats to meet with citizens on social media to talk about issues affecting societies. A critical opportunity is how we support everyone to engage with the evidence. Unfortunately, the events before that X space (with President Ruto) were much more potent than any scientific report.

However, we must consider the opportunities to be gained for future generations (or lost) in such situations. Young people, popularly known as Gen Z in Kenya during the ongoing protests, were able to use Generative AI to break down complex concepts in policy documents so that all could understand the purpose of their grievances, often in very short periods. This was yet another sign that my colleagues at the Center for Rapid Evidence Synthesis, Pan African Collective for Evidence, and Ethiopian Public Health Institute are on the right path to interrogate how digital technologies, such as Generative AI, could strengthen evidence to policy. An opportunity was lost, as this was fertile ground to synthesise and package several evidence briefs for Gen Zs and interested individuals. I refer to the evidence in its totality (comprehensive) and its meaning for the intended outcomes. Is it complete, consistent, trustworthy (often comes with how it was conducted), and relevant for everyone? I do not claim that these are all the questions, but a starting point to critically interact with the evidence and use it to guide our everyday decisions.

Everyone (almost) agrees that research evidence is valuable to humankind's progress, e.g., eradicating deadly diseases like smallpox—of course, except for the uncontacted Amazon tribes. However, ensuring that we pay attention to it is often strenuous. Several commentators have pointed out challenges with the use of language, packaging, and the disconnect research has from the “actual” issues faced by communities as some of the challenges. Additionally, the question of time is often in passing and usually acknowledgement without thought. However, if we make urgent decisions without interacting with the evidence, what are the chances that we will when the stakes are raised? It is known that generating evidence is time-consuming. The evidence likely arrives when the decisions are made and, hopefully, wait for another similar opportunity. For example, in 2022, while the exhaustion of COVID-19 was wearing down, Uganda had to deal with another Ebola outbreak. Although the Ebola outbreak in West Africa had advanced evidence for the potential treatments, the outbreak ended before the scientific world was confident about the efficacy of these treatments. More research was needed, but there was no time or opportunity for outbreaks to test these treatments. Even with some potential treatments approved, several bottlenecks, such as geopolitics, costs of drugs, and impossible logistic supply chains, make it nearly impossible for countries like Uganda to access and provide for their citizens without external support. What does this have to do with citizens' use of evidence? Even in such crises, assessing the evidence to inform our current decisions is possible. Digital tools could certainly make this much more efficient. However, these have to be developed and taught.

I was thinking about the tremendous progress achieved to bridge the gap between evidence and policy or practice, even for the citizens. It is the sand grains. I am proud to have been a part of this journey for nearly ten years. While I struggled to explain this to my mother, I am aware that this shows how much more we must do for evidence-use to become the norm, which is an enormous task. A task I am proud to be a part of and hopefully will be at the front for years to come.

About the author: Ismael Kawooya is a Senior Research Scientist and Head of Office at Uganda's Center for Rapid Evidence Synthesis (ACRES). He has seven years of experience engaging with policymakers at Uganda's national and sub-national levels to enhance access to high-quality and synthesised research and data in urgent situations, often within 28 days. He coordinates efforts to ensure the sustainability and scale of the rapid response service, supporting policymakers in health, reproductive health, clean energy, youth employment and climate change to improve equity, health and social outcomes in Uganda and the region.

He has grown to mentor and lead younger researchers at ACRES and in the East African region, set trends in applying methods and newer technologies, such as Artificial intelligence for EIPM, and champion the sustainability of institutions supporting EIPM within the region. Ismael has supported and mentored more than 110 researchers and policymakers in Tanzania, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Uganda, Cameroon, India, and Malaysia. He is also currently a co-investigator on a regional collaboration to mentor teams in Tanzania, Malawi, Ethiopia, and Uganda to scale up and/ or establish rapid response units to support EIPM within their contexts.

He has gained international recognition through the Cochrane Child Health Fellowship 2019, Emerging Voices for Global Health (EV4GH) 2022, and International Health Policy (IHP) Resident 2023 at the Institute for Tropical Medicine in Antwerp.

Ismael holds a bachelor’s degree in medicine and surgery and Masters in Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics from Makerere University.

Acknowledgements: The author(s) is solely responsible for the content of this article, including all errors or omissions; acknowledgements do not imply endorsement of the content. The author is grateful to Charity Chisoro for her guidance in preparing and finalising this article, as well as her editorial support.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in published blog posts, as well as any errors or omissions, are the sole responsibility of the author/s and do not represent the views of the Africa Evidence Network, its secretariat, advisory or reference groups, or its funders; nor does it imply endorsement by the afore-mentioned parties.

Suggested citation: Kawooya, I. (2024) Weaving through the Sand: How can evidence-informed decision-making work for all? Blog posting on 19 July 2024. Available at: https://www.africaevidencenetwork.org/en/learning-space/article/331