Ten features critical to regulate to ensure programme effectiveness

A learner who has been out-of-school for many months enrols in a flexible accelerated learning programme carefully designed meet their needs. They rebuild confidence, make rapid progress, and begin to see a route back into education. But they stall at the school gate. Sometimes the barrier is administrative. Sometimes it is cost, distance, stigma, or safety. Other times it is simply the absence of a clear pathway for what happens next.

Across Africa, this story is familiar, even if the names of the programmes differ: accelerated education, second-chance, catch-up, or bridging classes, remedial pathways, alternative provision. These pathways all exist to respond to real challenges: poverty, displacement, conflict, crisis, school closures, and the many reasons children and youth are excluded.

The headline finding is both sobering and hopeful: transition challenges are specific, predictable, and preventable. But prevention requires being explicit about where pathways break down, who is most affected, and who is responsible for strengthening each link.

But this is not only a story about learners already out of school. It is also about learners in school but at risk of leaving: children who are over-age for grade and falling behind, girls facing pregnancy-related exclusion, learners whose households face sudden income shocks, or those for whom safety, disability, distance, and discrimination make attendance fragile. Being out of school and being at risk of dropout are not separate issues. They are two points on the same pathway, and systems can plan for prevention and return as one joined-up agenda.

This “last mile” matters because the scale is enormous. Globally, there are 272 million out-of-school children and youth. African countries carry a disproportionate share of the challenge, alongside a persistent learning crisis. Governments and partners are investing in programmes that bring young people back to learning, and in reforms that aim to strengthen the quality of schooling. Yet too often, the bridge between these efforts is weak. Without clear transition pathways into and within formal schooling, progress becomes fragile: learners may re-engage, but still struggle to enrol, settle, and stay. And when retention inside the formal system is weak, that last mile becomes a revolving door.

One reason transitions remain neglected is that they are rarely measured. Only a small share of accelerated programmes track what happens to learners after completion. Metrics and definitions vary widely, with limited disaggregation to understand how gender, disability, or household location impacts learner pathways. This creates a blind spot: systems can’t count which learners move into, participate in, and learn in the next stage of education. Without this data, system leaders are unable to effectively plan for or fund transitions.

This is not a marginal problem. Based on the evidence we reviewed, fewer than half of learners in accelerated education may transition successfully into formal school, meaning not only enrolment but completion of at least the first year. In fragile and crisis contexts, the estimate is closer to four in ten. Importantly, transition alone is not the finish line: retention and learning make transitions meaningful. So, the practical question for education leaders becomes: how do we design systems so that all learners can enter, remain, progress, and complete their schooling?

To help decision-makers move from concern to action, Education.org built an evidence synthesis and guidance package for decision-makers, focused on supporting transitions from flexible learning pathways into and through formal schooling[1]. We developed this through our Locally Inclusive Framework for Education Decision-Making (LIFTED), which is designed to make evidence usable for real planning choices. We screened over 11,000 sources and quality-appraised 387, drawing on evidence from 68 countries and national policies from 50 countries. We also broadened what “counts” as evidence for decision-making, surfacing more operational and context-grounded insights, including substantially more evidence from authors and organisations in low- and middle-income countries. This matters for Africa because transition success is shaped as much by implementation realities as by policy intent.

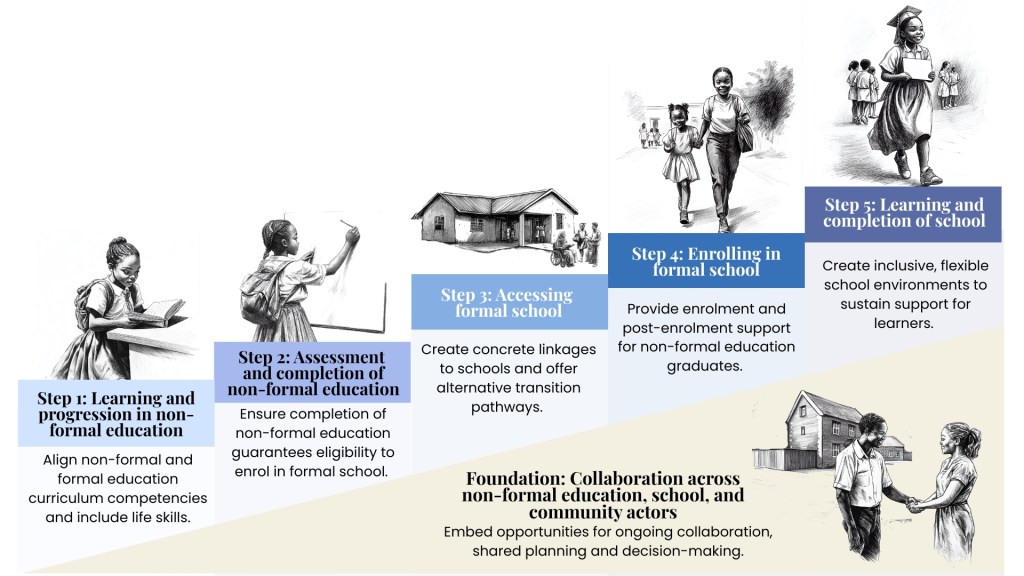

This is why we translated the synthesis into the STEP Framework for Supporting Transitions through Evidence-based Planning. STEP breaks the learner journey into five practical stages plus a cross-cutting foundation, so leaders can pinpoint what to fix and when. It is built for the practical decision points in education systems: sector dialogue, annual workplanning, programme design, budgeting, coordination with partners, and monitoring.

The STEP Framework, planning across the learner’s journey

The foundation is collaboration. Transitions are rarely delivered by one actor alone. They depend on alignment between non-formal education, formal schools, and communities; national intent and local practice; education services and the wider supports learners often need. When collaboration within the education ecosystem and learners’ environments is missing, responsibility is diffused, and young people pay the price.

STEP is paired with a practical toolkit: a questionnaire to help policy makers, implementers, and funders identify context-relevant priorities, and a menu of evidence-based strategies tailored to each role. The aim is to shift conversations from “we should do everything” to “what matters most now, what is feasible, and what can we sequence next?”, whether the goal is re-entry or dropout prevention. We have also been strengthening usability through a digital version of the STEP Tool, alongside an editable paper-based version for settings where digital access is limited.

As we developed the transition guidance, one pattern kept resurfacing: national averages can hide deep inequities, especially for girls and young women affected by poverty, rurality, displacement, disability, and restrictive gender norms. Girls facing the steepest barriers are often the most likely to drop out, and the least likely to have safe, supported pathways back into learning. These are not gaps that close on their own. They require deliberate, gender-responsive planning and implementation.

This is why we are preparing guidance focused on girls and young women. It builds on the evidence base but sharpens the focus on what it takes to deliver for girls and young women left behind. The purpose is practical: support governments and partners to identify who is being excluded, understand barriers at different stages of the pathway, and prioritise cost-effective actions that strengthen routes into and through formal schooling and alternative learning pathways. A key theme is measurement fit for purpose: gender-disaggregated data is a start, but monitoring must examine how gender intersects with poverty, disability, location, displacement, and other dimensions of marginalisation.

In parallel, we have enhanced the STEP tool, to help education teams engage in gender-transformative planning that enhances transitions and retention for girls and young women. As we start to deploy this tool, we are keen to explore practical ways to work with Africa Evidence Network members to champion and adapt STEP for use in different settings, whether through piloting it in a planning cycle, convening a learning session, or partnering on a “test and learn” effort that documents what helps the tool land in real decision spaces.

We want to hear learn from the AEN community: where can STEP have the most impact?

The solutions exist. The remaining challenge is making evidence usable in the moments where decisions are made, so every learner not only reaches school, but stays and thrives within it.

About the authors:

Giulia Di Filippantonio is a social scientist and education expert with 15 years of professional experience spanning programme design, management, research, and evaluation in development and humanitarian contexts. Her work is grounded in gender, equity, and inclusion, with deep expertise in women and girls’ education and protection, including in complex emergencies across Sub-Saharan Africa, and West Asia and North Africa. Prior to joining Education.org, she served in both leadership and technical roles with international NGOs and UN agencies, supporting teams to move from evidence and insight to practical, implementable change. Giulia holds a Master of International Affairs from the University of Trieste, with a specialisation in Oriental Studies from INALCO-Paris, and a Master of Education from the UCL Institute of Education. Her research in the West Asia and North Africa region, undertaken with Cairo University, the Al Ahram Centre for Political and Strategic Studies, the Arab Reform Forum, the Institute du Monde Arabe, and IREMMO, alongside ethnographic studies in Sierra Leone, explores inclusive policy and practice and the social norms shaping outcome.

Sophia D’Angelo is an inclusive education specialist and Director of Research at Education.org. With over 13 years of experiencing working in development and humanitarian contexts, she has a proven track record of conducting systematic and rapid evidence reviews, mappings, policy analyses, and primary research. A former teacher and teacher trainer, Sophia has worked for various organisations, including the World Bank, GPE, and INEE, and has published on a range of topics, including teacher professional development, gender-transformative and disability-inclusive education, EdTech, ECCE, and youth development. Based in the Dominican Republic, Sophia has extensive experience supporting programmes and policies in Latin America and the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. She holds a PhD and MPhil from the University of Cambridge’s The REAL Centre, and a BA from Princeton University.

Acknowledgements: The authors are solely responsible for the content of this article, including all errors or omissions; acknowledgements do not imply endorsement of the content.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in published blog posts, as well as any errors or omissions, are the sole responsibility of the author/s and do not represent the views of the Africa Evidence Network, its secretariat, advisory or reference groups, or its funders; nor does it imply endorsement by the afore-mentioned parties.

Suggested citation: Filippantonio, G.D & D’Angelo, S (2026) The Last Mile in Education: Designing Transition and Retention Pathways That Hold. Blog posting on 20 February 2026. Available at: https://africaevidencenetwork.org/the-last-mile-in-education-designing-transition-and-retention-pathways-that-hold/2026/02/20/

[1] This also builds on Education.org’s Accelerated Education Programmes: An evidence synthesis – Practical, contextually relevant guidance for those shaping policies and guidelines for AEPs built on existing evidence, and accompanying high-level guidance, Steering Through Storms: Five Recommendations for Education Leaders to Close the Learning Gap in Times of Crisis.